Towards a Smart Mix 2.0? Understanding Political Dynamics of Heterogeneity and Integration in Sustainable Supply Chain Governance

Philip Schleifer and Luc Fransen

Jul, 2024

#Sustainability standards

The adoption of new due diligence regulations in the European Union (EU) and other advanced economies has further increased the heterogeneity of global supply chain governance. In a recent study (Schleifer and Fransen 2022), we evaluate calls for a “smart mix 2.0” that combines public regulations with private governance instruments and new partnerships with producer countries. Private sustainability standards may compensate for public regulation weaknesses. Inclusion of Southern actors may promote more context-sensitive, inclusive, and comprehensive supply chain regulatory regimes. However, achieving cooperation among actors with diverging interests and power resources is challenging. A politically grounded analysis is crucial for identifying possibilities and limitations to integration in sustainable supply chain governance.

The increasing heterogeneity of sustainable supply chain governance

Over the past few decades, there has been a significant push to address human rights and environmental risks associated with global supply chains. This has led to the emergence of numerous public and private guidelines, standards, and regulations, increasing the heterogeneity of global supply chain governance (Fransen, Kolk, and Rivera-Santos 2019).

The International Labour Organization and the Organization for Economic Development and Cooperation, since the 1970s, have developed international guidelines designed to steer and exert pressure on transnational corporations, encouraging them to adopt responsible practices. During the 1980s attention in Europe and North America was drawn to corporate involvement with child labour, major environmental crises, and misleading corporate communication about health risks. In response to intensifying societal pressures, the business community formulated codes of conduct at both the firm and industry levels.

In the 1990s and 2000s, a next generation of private sustainability governance in form of multi-stakeholder initiatives took shape. These initiatives sought to foster collaboration between business and civil society actors. Certification became a notable feature of these initiatives, serving as indicators and mechanisms to incentivize compliance with voluntary sustainability standards. Today, third-party certification schemes like the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, the Fair Wear Foundation, and the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance certify millions of farms, factories, and mines around the world.

In recent years, two other notable regulatory trends have influenced the landscape of sustainable supply chain governance, adding further complexity. Firstly, historically, sustainability standards in global supply chains primarily originated from advanced economies in the Global North. However, concerns about potential loss of sovereignty in this critical policy area have spurred government and industry actors in major producer countries like Brazil, Indonesia, and South Africa to develop their own national sustainability standards and certification schemes. Secondly, there has been a noticeable transition from voluntary private governance towards mandatory public supply chain regulations in advanced economies. This shift signifies a growing recognition of the need for enforceable measures to ensure responsible practices throughout global supply chains. Within the EU, for instance, several significant supply chain laws have been introduced in recent years. These include the EU Conflict Minerals Regulation (2017), the EU Deforestation Regulation (2023), and the anticipated EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (expected in 2024).

The International Labour Organization and the Organization for Economic Development and Cooperation, since the 1970s, have developed international guidelines designed to steer and exert pressure on transnational corporations, encouraging them to adopt responsible practices. During the 1980s attention in Europe and North America was drawn to corporate involvement with child labour, major environmental crises, and misleading corporate communication about health risks. In response to intensifying societal pressures, the business community formulated codes of conduct at both the firm and industry levels.

In the 1990s and 2000s, a next generation of private sustainability governance in form of multi-stakeholder initiatives took shape. These initiatives sought to foster collaboration between business and civil society actors. Certification became a notable feature of these initiatives, serving as indicators and mechanisms to incentivize compliance with voluntary sustainability standards. Today, third-party certification schemes like the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, the Fair Wear Foundation, and the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance certify millions of farms, factories, and mines around the world.

In recent years, two other notable regulatory trends have influenced the landscape of sustainable supply chain governance, adding further complexity. Firstly, historically, sustainability standards in global supply chains primarily originated from advanced economies in the Global North. However, concerns about potential loss of sovereignty in this critical policy area have spurred government and industry actors in major producer countries like Brazil, Indonesia, and South Africa to develop their own national sustainability standards and certification schemes. Secondly, there has been a noticeable transition from voluntary private governance towards mandatory public supply chain regulations in advanced economies. This shift signifies a growing recognition of the need for enforceable measures to ensure responsible practices throughout global supply chains. Within the EU, for instance, several significant supply chain laws have been introduced in recent years. These include the EU Conflict Minerals Regulation (2017), the EU Deforestation Regulation (2023), and the anticipated EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (expected in 2024).

Towards a smart mix 2.0?

To effectively navigate the complexities of regulating global supply chains, there has been much discussion about the need for employing a “smart mix of measures.” This concept, initially focused on combinations of voluntary private and mandatory public regulatory instruments, has garnered significant attention in debates on human rights due diligence. Notably, it was John Ruggie (2011), a scholar-turned-policymaker, who introduced the idea of a smart mix of measures to advance the implementation of the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

The underlying idea of smart mixes revolves around acknowledging that both voluntary private governance and mandatory public regulation possess inherent strengths and weaknesses. By generating productive interactions between these instruments, it is hoped to address and compensate for these limitations, ultimately leading to enhanced regulatory performance. For example, private sustainability standards can provide public regulators and companies with valuable information during the due diligence process, support the extraterritorial implementation of supply chain laws, and address additional sustainability issues beyond what is covered by public regulations. Conversely, public regulators can contribute to improving the effectiveness of private sustainability standards through various means such as providing relevant information, fostering capacity building, offering financial support, and granting legal recognition.

While the discussion inspired by Ruggie has primarily focused on bridging the public-private divide in sustainable supply chain governance, there has been an expansion of the smart mix debate in recent years. Particularly in Europe, the formulation of the EU Deforestation Regulation has sparked a vibrant policy discussion surrounding the importance of partnerships and supportive measures on the supply side of global production networks (TFA 2020). These measures aim to facilitate effective on-the-ground implementation, establish local legitimacy, and mitigate unintended consequences for vulnerable groups in producer countries.

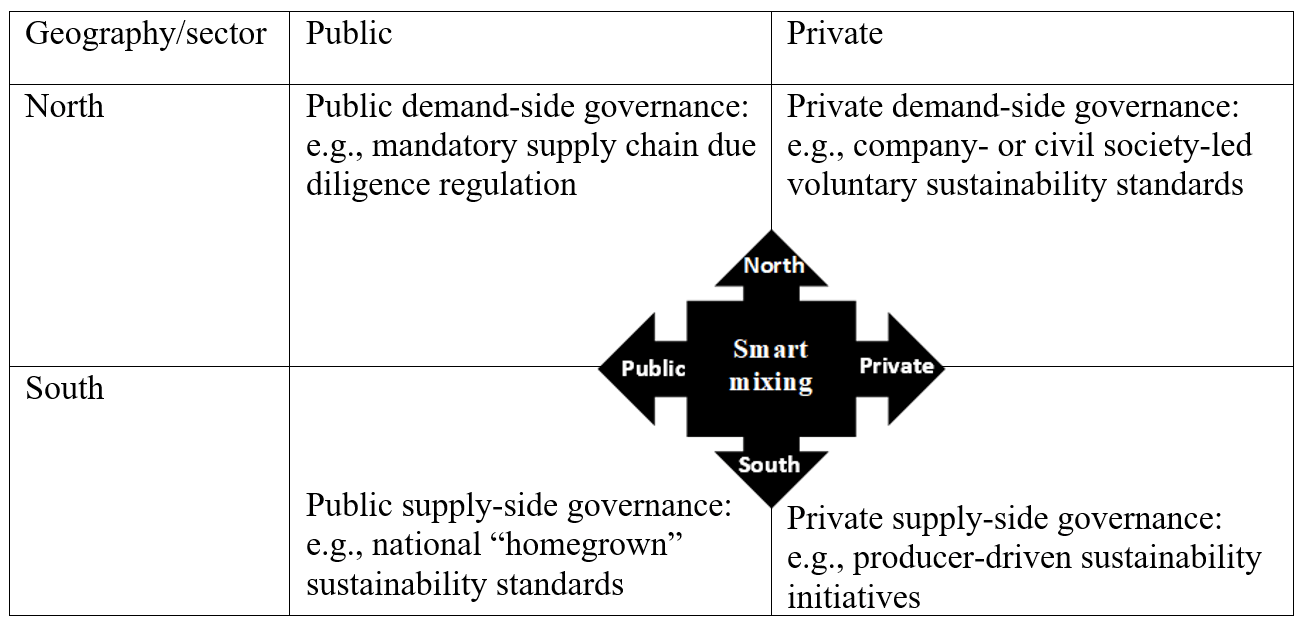

To capture the evolving smart mix debate, we coined the term smart mix 2.0, which, in addition to public-private complementarities, involves the integration of regulatory instruments across the demand side and supply side of global supply chains, often linked to the “North” and “South” in the world economy (see Table).

The underlying idea of smart mixes revolves around acknowledging that both voluntary private governance and mandatory public regulation possess inherent strengths and weaknesses. By generating productive interactions between these instruments, it is hoped to address and compensate for these limitations, ultimately leading to enhanced regulatory performance. For example, private sustainability standards can provide public regulators and companies with valuable information during the due diligence process, support the extraterritorial implementation of supply chain laws, and address additional sustainability issues beyond what is covered by public regulations. Conversely, public regulators can contribute to improving the effectiveness of private sustainability standards through various means such as providing relevant information, fostering capacity building, offering financial support, and granting legal recognition.

While the discussion inspired by Ruggie has primarily focused on bridging the public-private divide in sustainable supply chain governance, there has been an expansion of the smart mix debate in recent years. Particularly in Europe, the formulation of the EU Deforestation Regulation has sparked a vibrant policy discussion surrounding the importance of partnerships and supportive measures on the supply side of global production networks (TFA 2020). These measures aim to facilitate effective on-the-ground implementation, establish local legitimacy, and mitigate unintended consequences for vulnerable groups in producer countries.

To capture the evolving smart mix debate, we coined the term smart mix 2.0, which, in addition to public-private complementarities, involves the integration of regulatory instruments across the demand side and supply side of global supply chains, often linked to the “North” and “South” in the world economy (see Table).

Table: A “Smart Mix 2.0” for Sustainable Global Supply Chains

Proponents of the smart mix agenda argue that combining public-private and demand-side and supply-side governance instruments create complementarities that enhance regulatory effectiveness and address unintended consequences in producer countries. However, what are the possibilities and limitations of integrating sustainable supply chain governance in this way? To find an answer to this question, we argue that a politically grounded analysis beyond the functionalist smart mix debate is needed (Kinderman 2016). Such an analysis furthers understanding of how industry-specific power and interest constellations and histories of conflict shape interactions among public and private and Northern and Southern governance actors in a policy area and supply chain setting.

Evidence from the palm oil supply chain

With a focus on the EU Deforestation Regulation, our study explores the dynamics of “smart mix politics” In the EU-Indonesia palm oil supply chain. The palm oil industry has long been a forerunner in sustainable supply chain governance, making it an instructive case for studying questions of regulatory heterogeneity and integration.

In assessing the public-private dimension of the smart mix concept introduced above, we describe the development of hybrid regime “light,” in which voluntary private governance instruments play only a limited role. Although their use is permitted, EU regulators have opted not to endorse, support, or formally recognize private certification schemes under the EU Deforestation Regulation. Our analysis identifies several interrelated reasons for this shift towards a more public-centric governance mix: the negative experience with the use of private certification schemes in other supply chain settings, opposition from non-governmental organizations against the integration of voluntary instruments, and evolving perspectives within EU regulatory bodies regarding the efficiency and effectiveness of hybrid governance models.

Turning to North-South dimension of the smart mix debate, we observe that transnational governance interactions in the palm oil sector have often been fraught with conflicts. These conflicts manifest in various ways, such as regulatory competition between global and domestic certification schemes, the curbing of transnational private governance initiatives by the Indonesian government, and the political controversies surrounding EU unilateralism and its decision to prohibit the use of imported palm oil for biofuel production. Differences over policy design and sensitivities around national sovereignty, often entangled in colonial histories, contribute to these conflicts.

One area in which we observe some progress in productively integrating governance actors from North and South are efforts to link global buyers of agricultural commodities to local multi-stakeholder initiatives. Recent years have seen a flurry of activity by local governments and civil society organizations in Indonesia to develop governance mechanisms to implement sustainability standards across entire jurisdictions (e.g., a province or district), as opposed to individual supply chains (Schleifer 2023). This has been accompanied by efforts of international standard setting bodies, such as the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, to develop verification systems to facilitate “jurisdictional sourcing”, in which well-performing jurisdictions are rewarded by global buyers through preferential sourcing agreements. Recent commitments by major consumer goods companies to step up their engagement in these initiatives are a positive development. However, the jurisdictional sourcing approach brings its own challenges, including coordination problems and power asymmetries in complex multistakeholder settings.

In sum, when, where, and how is “smart mixing” possible? Moving beyond functionalist arguments about the need to create regulatory complementarities across sectors and geographies, our case study of the palm oil industry shows that answering these questions requires close analysis of the political dynamics that drive heterogeneity and integration in a given supply chain setting.

In assessing the public-private dimension of the smart mix concept introduced above, we describe the development of hybrid regime “light,” in which voluntary private governance instruments play only a limited role. Although their use is permitted, EU regulators have opted not to endorse, support, or formally recognize private certification schemes under the EU Deforestation Regulation. Our analysis identifies several interrelated reasons for this shift towards a more public-centric governance mix: the negative experience with the use of private certification schemes in other supply chain settings, opposition from non-governmental organizations against the integration of voluntary instruments, and evolving perspectives within EU regulatory bodies regarding the efficiency and effectiveness of hybrid governance models.

Turning to North-South dimension of the smart mix debate, we observe that transnational governance interactions in the palm oil sector have often been fraught with conflicts. These conflicts manifest in various ways, such as regulatory competition between global and domestic certification schemes, the curbing of transnational private governance initiatives by the Indonesian government, and the political controversies surrounding EU unilateralism and its decision to prohibit the use of imported palm oil for biofuel production. Differences over policy design and sensitivities around national sovereignty, often entangled in colonial histories, contribute to these conflicts.

One area in which we observe some progress in productively integrating governance actors from North and South are efforts to link global buyers of agricultural commodities to local multi-stakeholder initiatives. Recent years have seen a flurry of activity by local governments and civil society organizations in Indonesia to develop governance mechanisms to implement sustainability standards across entire jurisdictions (e.g., a province or district), as opposed to individual supply chains (Schleifer 2023). This has been accompanied by efforts of international standard setting bodies, such as the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, to develop verification systems to facilitate “jurisdictional sourcing”, in which well-performing jurisdictions are rewarded by global buyers through preferential sourcing agreements. Recent commitments by major consumer goods companies to step up their engagement in these initiatives are a positive development. However, the jurisdictional sourcing approach brings its own challenges, including coordination problems and power asymmetries in complex multistakeholder settings.

In sum, when, where, and how is “smart mixing” possible? Moving beyond functionalist arguments about the need to create regulatory complementarities across sectors and geographies, our case study of the palm oil industry shows that answering these questions requires close analysis of the political dynamics that drive heterogeneity and integration in a given supply chain setting.

References

Fransen, Luc, Ans Kolk, and Miguel Rivera-Santos. 2019. "The Multiplicity of International Corporate Social Responsibility Standards: Implications for Global Value Chain Governance." Multinational Business Review 27 (4):397-426.

Kinderman, Daniel. 2016. "Time for a Reality Check: Is Business Willing to Support a Smart Mix of Complementary Regulation in Private Governance?" Policy and Society 35 (1):29-42.

Ruggie, John. 2011. "Report of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on the Issue of Human Rights and Transnational Corporations and other Business Enterprises: Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Implementing the United Nations ‘Protect, Respect and Remedy’ Framework." Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 29 (2):224-253.

Schleifer, Philip. 2023. "Beyond Islands of Sustainability? Opportunities and Challenges of Jurisdictional Approaches in Tropical Forest Governance." In Global Environmental Politics in a Turbulent Era, edited by Peter Dauvergne and Leah Shipton, 156-168. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Schleifer, Philip, and Luc Fransen. 2022. "Towards a Smart Mix 2.0: Harnessing Regulatory Heterogeneity for Sustainable Global Supply Chains, SWP Working Paper, Research Network Sustainable Global Supply Chains, WP NR. 04 AUGUST 2022."

TFA. 2020. "Collective Position Paper on EU Action to Protect and Restore the World's Forests: Proposal for a "Smart Mix" of Measures." https://www.theconsumergoodsforum.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/TFA-EU-Position-Paper-201209.pdf.

Fransen, Luc, Ans Kolk, and Miguel Rivera-Santos. 2019. "The Multiplicity of International Corporate Social Responsibility Standards: Implications for Global Value Chain Governance." Multinational Business Review 27 (4):397-426.

Kinderman, Daniel. 2016. "Time for a Reality Check: Is Business Willing to Support a Smart Mix of Complementary Regulation in Private Governance?" Policy and Society 35 (1):29-42.

Ruggie, John. 2011. "Report of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on the Issue of Human Rights and Transnational Corporations and other Business Enterprises: Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Implementing the United Nations ‘Protect, Respect and Remedy’ Framework." Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 29 (2):224-253.

Schleifer, Philip. 2023. "Beyond Islands of Sustainability? Opportunities and Challenges of Jurisdictional Approaches in Tropical Forest Governance." In Global Environmental Politics in a Turbulent Era, edited by Peter Dauvergne and Leah Shipton, 156-168. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Schleifer, Philip, and Luc Fransen. 2022. "Towards a Smart Mix 2.0: Harnessing Regulatory Heterogeneity for Sustainable Global Supply Chains, SWP Working Paper, Research Network Sustainable Global Supply Chains, WP NR. 04 AUGUST 2022."

TFA. 2020. "Collective Position Paper on EU Action to Protect and Restore the World's Forests: Proposal for a "Smart Mix" of Measures." https://www.theconsumergoodsforum.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/TFA-EU-Position-Paper-201209.pdf.