GVCs and COVID-19: Lessons thus far from trade during a global pandemic

Robert B. Koopman

Apr 19, 2024 01:52 AM

#Trade and FDI

One year into the global COVID-19 pandemic, global trade and global value chains have held up admirably well considering the overall economic impacts in most countries.

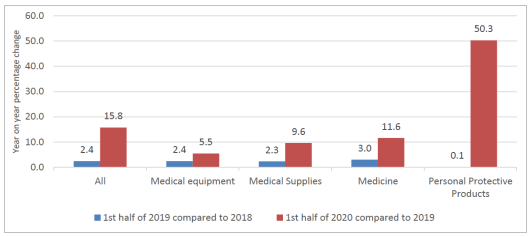

The COVID-19 pandemic led to shortages of medical equipment and pharmaceutical products in many countries as demand spikes exceeded existing supply and production capacity. Most countries are dependent on imports for critical goods, such as personal protective equipment and various medicines, from a relatively small number of countries. WTO data shows that Germany, the US, and Switzerland supply 35% of medical products to the world, and that China, Germany, and the US export 40% of personal protective products. In light of unmet peak demand, we saw bidding wars and export restrictions that raised the price of many pandemic-related critical goods. But through mid-year 2020, exports of many critical goods had soared compared to the previous year (see figure 1.)

The COVID-19 pandemic led to shortages of medical equipment and pharmaceutical products in many countries as demand spikes exceeded existing supply and production capacity. Most countries are dependent on imports for critical goods, such as personal protective equipment and various medicines, from a relatively small number of countries. WTO data shows that Germany, the US, and Switzerland supply 35% of medical products to the world, and that China, Germany, and the US export 40% of personal protective products. In light of unmet peak demand, we saw bidding wars and export restrictions that raised the price of many pandemic-related critical goods. But through mid-year 2020, exports of many critical goods had soared compared to the previous year (see figure 1.)

Figure 1. Trade in medical goods has increased significantly in COVID-19

Percentage change of trade in medical goods in the first half of 2019 and the first half of 2020 compared to the same period of previous year

While total world trade declined by 14% in the first half of 2020 compared to the same time period in 2019, imports and exports of medical goods increased by 16%, reaching US$ 1,139 billion in value. Trade played a critical role in meeting skyrocketing demand for products considered critical in the COVID-19 pandemic, with global trade in these products growing by 29%. Total imports of face protection products in the first half of 2020 increased by 90% compared to the same period last year. Trade in textile face masks has grown about six-fold. China was the top supplier of face masks, accounting for 56% of world exports. To ramp up mask manufacturing, China leaned heavily on imports of intermediate input materials: its imports of non-woven fabric tripled in April 2020 compared with the same month of 2019, with Japan and the United States as the leading suppliers. China was also the sixth-largest importer of face masks in the first half of 2020.

The initial health-related lockdown in Wuhan and other parts of China and the border lockdowns imposed by most countries resulted in transport delays and interruptions of production in complex value chains because of missing intermediates. These disruptions increased public awareness about the risks associated with globally fragmented production processes. As a result, many policy makers and analysts argued for reshoring supply chains and the production of critical goods to improve supply chain resilience and limit reliance on imports. These calls were often reinforced by populist calls for a return of offshored manufacturing activity and jobs.

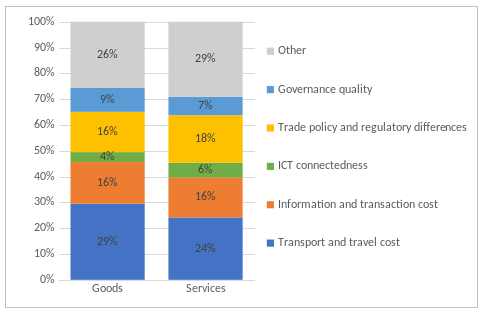

What are the lessons of the pandemic for global value chains? Will there be significant reshoring, more nearshoring, redistribution of global supply chains, or maintaining of the status quo? Following the growing trade tensions with the abrupt US policy changes under the Trump administration resulting in higher tariffs being applied to China but also other countries, we observed significant rises in trade policy uncertainty (Baker et al., 2019), but with little evidence of reshoring. Since the main value of the WTO, as Koopman et al. (2020) argue, is to increase certainty and transparency, the multilateral trading system can play a key role in times of uncertainty. The authors suggest that membership of the WTO locks in beneficial reform and has a public good nature that also fosters trade with non-members. IMF research has suggested that trade growth is largely driven by factors other than trade-related policies (IMF 2016) and WTO research on trade costs clearly demonstrates (see figure 2) that trade policies and regulatory differences across countries explain only part of trade cost variations across countries and sectors, with transport and travel costs and information and transaction costs accounting for equal or greater shares (Rubinova and Sebti, 2021). While tariffs clearly play a role in how and where companies align value chains, it is also clear that many other factors contribute to that decision making.

The initial health-related lockdown in Wuhan and other parts of China and the border lockdowns imposed by most countries resulted in transport delays and interruptions of production in complex value chains because of missing intermediates. These disruptions increased public awareness about the risks associated with globally fragmented production processes. As a result, many policy makers and analysts argued for reshoring supply chains and the production of critical goods to improve supply chain resilience and limit reliance on imports. These calls were often reinforced by populist calls for a return of offshored manufacturing activity and jobs.

What are the lessons of the pandemic for global value chains? Will there be significant reshoring, more nearshoring, redistribution of global supply chains, or maintaining of the status quo? Following the growing trade tensions with the abrupt US policy changes under the Trump administration resulting in higher tariffs being applied to China but also other countries, we observed significant rises in trade policy uncertainty (Baker et al., 2019), but with little evidence of reshoring. Since the main value of the WTO, as Koopman et al. (2020) argue, is to increase certainty and transparency, the multilateral trading system can play a key role in times of uncertainty. The authors suggest that membership of the WTO locks in beneficial reform and has a public good nature that also fosters trade with non-members. IMF research has suggested that trade growth is largely driven by factors other than trade-related policies (IMF 2016) and WTO research on trade costs clearly demonstrates (see figure 2) that trade policies and regulatory differences across countries explain only part of trade cost variations across countries and sectors, with transport and travel costs and information and transaction costs accounting for equal or greater shares (Rubinova and Sebti, 2021). While tariffs clearly play a role in how and where companies align value chains, it is also clear that many other factors contribute to that decision making.

Figure 2: Determinants of trade costs, percentage of bilateral variation

The challenge for firms, and governments, is to balance a risk-versus-efficiency trade-off. Firms’ optimization processes can no longer focus purely on efficiency (factor cost minimization) gains and must now put more weight on risks (rising policy and economic uncertainty). As Baldwin (2016) and others have pointed out, improvements in communication technology, lower uncertainty due to large numbers of international economic agreements, and falling domestic and international trade costs, partly due to the international agreements and partly due to technological improvements, essentially allowed firms to focus on efficiency gains through outsourcing domestically and offshore. This fragmentation of production, often building on domestic fragmentation of supply chains, spread globally as international trade costs fell relative to domestic trade costs (Beverelli et al. 2019).

While supply chain risks have always remained, exemplified by events like the Fukushima disaster or US Gulf Coast hurricanes, they were viewed as more naturally occurring random events rather than systemic policy risks. Assessments of supply chain disruptions initially focused more on these kinds of events (see for example Simchi-Levi et al. 2014). Yet, with the advent of the US-China trade conflict in 2017, and the broader US efforts to disrupt existing international commitments on trade, and finally with a major global health pandemic in the form of COVID-19, firms are likely to reconsider their traditional focus on pursuing pure efficiency in supply chains and consider how best to manage risks in those supply chains. Governments, held accountable by their citizenry, also need to consider how best to manage these risks in the form of comprehensive health policies coherent with economic policies, and combined with efficient use of taxpayer and private sector resources to manage future crises.

Recent research by Lund et al. (2020) examines how firms are responding to these rising risks by estimating how much in annual profits might be lost due to supply chain disruptions. This kind of effort puts a value on what a maximum risk mitigation strategy might be worth to a firm, given that firms are not likely to spend more on that strategy than the foregone profits. Accenture (2020), along with other firms such as Deloitte (2020), have started to deploy supply chain risk assessment tools for firms to be able to identify potential weak links in their supply chains. Governments are also conducting such exercises, as seen in recent work by Global Affairs Canada (Boileau, 2020) and a request from the United States House Ways and Means Committee to the United States International Trade Commission (USITC) to conduct an assessment of US supply chains for critical goods (USITC 2020), which was followed by yet another request for an even deeper study.

Thus far, global trade data following the US-China trade conflict suggests that the more typical response of firms has been to diversify their global supply chains to other countries rather than to re-shore production. Similarly, the response to the COVID-19 pandemic shows that trade and many GVCs have been relatively resilient, after initial disruptions and declines, with merchandise trade recovering to its December 2019 level in November of 2020. Given the very large decline in global GDP in 2020, the trade decline is much smaller relative to the GDP decline than in past downturns, and particularly compared the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-9. At of the end of 2020, trade declined about twice as much as GDP, while trade declined 6 times the decline in GDP during the great financial crisis. Despite the wide-scale disruptions to the movement of goods and people, and significant labor market disruptions for production, trade and global value chains remain relatively robust, at least in the mid-term.

It appears that firms, thus far, see opportunities to manage the rising risks from either policy uncertainty or a global health crisis by reorienting and diversifying their supply chains rather than reshoring. In some cases, governments are supporting domestic firms in realigning their foreign supply chains (Japan) and others are advertising that their economies provide a new alternative location for shifting supply chains (India, Mexico) from over-reliance on China.

One might argue that diversification from over-reliance on China had already started and was likely to occur over the longer term as China’s economy rebalanced from its historical reliance on investment and manufacturing as a source of growth to consumption and services (World Bank, 2013). Rising wages, increasing domestic regulations, and a planned transition to higher value-added activities had already seen significant outward FDI from China into other, lower wage, countries (Rosen and Hanemann, 2009). A recent examination of China’s potential transition to its 2030 goals suggests that if the transition is successful, and China’s savings rate declines and consumption increases, China’s role in the global economy would change substantially, moving from a large source of next exports, to a substantial importer, and potentially reducing its historical position in global and bilateral imbalances (Bekkers et al., 2021). Should such a change actually play out, it would be reinforcing the kinds of realignments of global supply chains we have observed over the past few years.

What lessons might we draw from the research on GVCs and determinants of trade flows in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic? Global value chains have developed due to the rapid evolution of technology, international agreements on trade and investment, and the ability to move production to low cost countries. Trade policies and their related trade costs do play a role in the firm calculations but typically other factors drive trade growth and GVC developments. Increasingly, firms have included the potential of rising costs related to supply chain disruption risks to their calculus, and not just pure cost efficiency. COVID-19 has added a global health-related risk element to these calculations, but the risk-versus-efficiency trade-off has yet to suggest a move to re-on-shoring of production, but rather appears to be leading to more re-alignment of global supply chains, reinforcing global trends already being observed for other reasons prior to Covid-19.

While supply chain risks have always remained, exemplified by events like the Fukushima disaster or US Gulf Coast hurricanes, they were viewed as more naturally occurring random events rather than systemic policy risks. Assessments of supply chain disruptions initially focused more on these kinds of events (see for example Simchi-Levi et al. 2014). Yet, with the advent of the US-China trade conflict in 2017, and the broader US efforts to disrupt existing international commitments on trade, and finally with a major global health pandemic in the form of COVID-19, firms are likely to reconsider their traditional focus on pursuing pure efficiency in supply chains and consider how best to manage risks in those supply chains. Governments, held accountable by their citizenry, also need to consider how best to manage these risks in the form of comprehensive health policies coherent with economic policies, and combined with efficient use of taxpayer and private sector resources to manage future crises.

Recent research by Lund et al. (2020) examines how firms are responding to these rising risks by estimating how much in annual profits might be lost due to supply chain disruptions. This kind of effort puts a value on what a maximum risk mitigation strategy might be worth to a firm, given that firms are not likely to spend more on that strategy than the foregone profits. Accenture (2020), along with other firms such as Deloitte (2020), have started to deploy supply chain risk assessment tools for firms to be able to identify potential weak links in their supply chains. Governments are also conducting such exercises, as seen in recent work by Global Affairs Canada (Boileau, 2020) and a request from the United States House Ways and Means Committee to the United States International Trade Commission (USITC) to conduct an assessment of US supply chains for critical goods (USITC 2020), which was followed by yet another request for an even deeper study.

Thus far, global trade data following the US-China trade conflict suggests that the more typical response of firms has been to diversify their global supply chains to other countries rather than to re-shore production. Similarly, the response to the COVID-19 pandemic shows that trade and many GVCs have been relatively resilient, after initial disruptions and declines, with merchandise trade recovering to its December 2019 level in November of 2020. Given the very large decline in global GDP in 2020, the trade decline is much smaller relative to the GDP decline than in past downturns, and particularly compared the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-9. At of the end of 2020, trade declined about twice as much as GDP, while trade declined 6 times the decline in GDP during the great financial crisis. Despite the wide-scale disruptions to the movement of goods and people, and significant labor market disruptions for production, trade and global value chains remain relatively robust, at least in the mid-term.

It appears that firms, thus far, see opportunities to manage the rising risks from either policy uncertainty or a global health crisis by reorienting and diversifying their supply chains rather than reshoring. In some cases, governments are supporting domestic firms in realigning their foreign supply chains (Japan) and others are advertising that their economies provide a new alternative location for shifting supply chains (India, Mexico) from over-reliance on China.

One might argue that diversification from over-reliance on China had already started and was likely to occur over the longer term as China’s economy rebalanced from its historical reliance on investment and manufacturing as a source of growth to consumption and services (World Bank, 2013). Rising wages, increasing domestic regulations, and a planned transition to higher value-added activities had already seen significant outward FDI from China into other, lower wage, countries (Rosen and Hanemann, 2009). A recent examination of China’s potential transition to its 2030 goals suggests that if the transition is successful, and China’s savings rate declines and consumption increases, China’s role in the global economy would change substantially, moving from a large source of next exports, to a substantial importer, and potentially reducing its historical position in global and bilateral imbalances (Bekkers et al., 2021). Should such a change actually play out, it would be reinforcing the kinds of realignments of global supply chains we have observed over the past few years.

What lessons might we draw from the research on GVCs and determinants of trade flows in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic? Global value chains have developed due to the rapid evolution of technology, international agreements on trade and investment, and the ability to move production to low cost countries. Trade policies and their related trade costs do play a role in the firm calculations but typically other factors drive trade growth and GVC developments. Increasingly, firms have included the potential of rising costs related to supply chain disruption risks to their calculus, and not just pure cost efficiency. COVID-19 has added a global health-related risk element to these calculations, but the risk-versus-efficiency trade-off has yet to suggest a move to re-on-shoring of production, but rather appears to be leading to more re-alignment of global supply chains, reinforcing global trends already being observed for other reasons prior to Covid-19.

References:

Accenture (2020). Repurpose Your Supply Chain. Seven Ways to Support the Global Response to COVID-19 and Reshape Supply Chains for the Future. Available at https://www.accenture.com/_acnmedia/PDF-121/Accenture-COVID-19-Repurpose-Supply-Chain.pdf#zoom=40.

Baker, S., Bloom, N. & Davis, S. (2019). The Extraordinary Rise in Trade Policy Uncertainty, VoxEU (17 September).

Baldwin, R. (2016). The Great Convergence, Information Technology and the New Globalization. MA: Harvard University Press.

Bekkers, E., Koopman, R., & Rêgo, C. (2021). Structural Change in the Chinese Economy and Changing Trade Relations with the World. China Economic Review. 65.

Beverelli, C., Stolzenburg, V., Koopman, R., & Neumuller S., (2019). Domestic Value Chains as Stepping Stones to Global Value Chain Integration. The World Economy, 42(5).

Boileau, David (2020). Potential Vulnerabilities for Canadian Industries within Cross-border Supply Chains. Global Affairs Canada, Office of the Chief Economist. Working paper.

Deloitte (2020). COVID-19: Managing Supply Chain Risk and Disruption, Deloitte Canada.

International Monetary Fund, 2016. World Economic Outlook, Chapter 2, Global Trade: What’s Behind the Slowdown, October.

Koopman, R., Hancock, J., Piermartini, R., & Bekkers, E., (2020). The Value of the WTO, Journal of Policy Modeling, 42(4).

Lund, S., Manyika, J., Woetzel, J., Barriball, E., Krishnan, M., Alicke, K., Birshan, M., George, K., Smit, S., Swan, D. & Hutzler, K. (2020). Risk, Resilience, and Rebalancing in Global Value Chains, McKinsey & Company.

Rosen, D. and Hanemann, T. (2009). China’s Changing Outbound Foreign Direct Investment Profile: Drivers and Policy Implications, Petersen Institute for International Economics Policy Brief PB09-14.

Rubinova, S. and Sebti, M., (2021). The WTO Global Trade Costs Index and Its Determinants, Manuscript date: 18 January 2021.

Simchi-Levi, D., Schmidt, W. & Wei, Y. (2014). From Superstorms to Factory Fires: Managing Unpredictable Supply-Chain Disruptions, Harvard Business Review, January-February.

United States International Trade Commission (2020). COVID-19 Related Goods: The U.S. Industry, Market, Trade, and Supply Chain Challenges, Publication Number: 5145, December.

World Bank; Development Research Center of the State Council, the People’s Republic of China. (2013). China 2030: Building a Modern, Harmonious, and Creative Society. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Trade Organization (WTO), (2020). Trade in Medical Goods in the Context of Tackling COVID-19: Developments in the First Half of 2020. WTO COVID-19 Information Note, December. Found at: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/medical_goods_update_e.pdf.

Accenture (2020). Repurpose Your Supply Chain. Seven Ways to Support the Global Response to COVID-19 and Reshape Supply Chains for the Future. Available at https://www.accenture.com/_acnmedia/PDF-121/Accenture-COVID-19-Repurpose-Supply-Chain.pdf#zoom=40.

Baker, S., Bloom, N. & Davis, S. (2019). The Extraordinary Rise in Trade Policy Uncertainty, VoxEU (17 September).

Baldwin, R. (2016). The Great Convergence, Information Technology and the New Globalization. MA: Harvard University Press.

Bekkers, E., Koopman, R., & Rêgo, C. (2021). Structural Change in the Chinese Economy and Changing Trade Relations with the World. China Economic Review. 65.

Beverelli, C., Stolzenburg, V., Koopman, R., & Neumuller S., (2019). Domestic Value Chains as Stepping Stones to Global Value Chain Integration. The World Economy, 42(5).

Boileau, David (2020). Potential Vulnerabilities for Canadian Industries within Cross-border Supply Chains. Global Affairs Canada, Office of the Chief Economist. Working paper.

Deloitte (2020). COVID-19: Managing Supply Chain Risk and Disruption, Deloitte Canada.

International Monetary Fund, 2016. World Economic Outlook, Chapter 2, Global Trade: What’s Behind the Slowdown, October.

Koopman, R., Hancock, J., Piermartini, R., & Bekkers, E., (2020). The Value of the WTO, Journal of Policy Modeling, 42(4).

Lund, S., Manyika, J., Woetzel, J., Barriball, E., Krishnan, M., Alicke, K., Birshan, M., George, K., Smit, S., Swan, D. & Hutzler, K. (2020). Risk, Resilience, and Rebalancing in Global Value Chains, McKinsey & Company.

Rosen, D. and Hanemann, T. (2009). China’s Changing Outbound Foreign Direct Investment Profile: Drivers and Policy Implications, Petersen Institute for International Economics Policy Brief PB09-14.

Rubinova, S. and Sebti, M., (2021). The WTO Global Trade Costs Index and Its Determinants, Manuscript date: 18 January 2021.

Simchi-Levi, D., Schmidt, W. & Wei, Y. (2014). From Superstorms to Factory Fires: Managing Unpredictable Supply-Chain Disruptions, Harvard Business Review, January-February.

United States International Trade Commission (2020). COVID-19 Related Goods: The U.S. Industry, Market, Trade, and Supply Chain Challenges, Publication Number: 5145, December.

World Bank; Development Research Center of the State Council, the People’s Republic of China. (2013). China 2030: Building a Modern, Harmonious, and Creative Society. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Trade Organization (WTO), (2020). Trade in Medical Goods in the Context of Tackling COVID-19: Developments in the First Half of 2020. WTO COVID-19 Information Note, December. Found at: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/medical_goods_update_e.pdf.